Exploitation or Opportunity?

World War II created many opportunities for women to join the work force, as they filled labor shortages caused by men heading to the front lines. However, when soldiers returned home after the war, women were expected to leave their jobs and return to the business of homemaking.

For many women, that was not ideal. Women had been able to make their own money, although their wages were lower than what men were paid, they wanted to continue to have a measure of financial independence.

After the war, the average pay for skilled women laborers was around $30 a week. For men, that number averaged $51 a week. But for a Hormel Girl, the starting wage was $50 per week, along with all tour expenses paid— including hotels, transportation, uniforms, and meals. If the women had higher sales, they could win bonuses of up to $25 each week. Hormel Girls also received a paid ten-day vacation every three months and an all-expense paid trip home. Some months, Hormel Girls could go home with over $200, while other working women were still making less than they did during the war.

While the Hormel Girls had been created as a marketing tool to increase sales—at times monetizing their military service and femininity—the financial benefits for the women in the group was clear, creating a rare opportunity for the time.

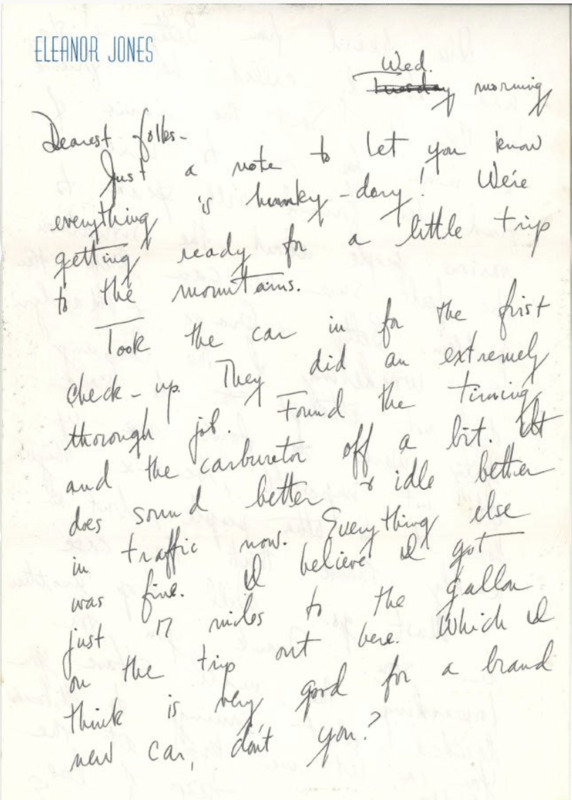

The Hormel Girls could use their higher income for necessities, as well as the finer things. In a letter to her parents, Eleanor writes of her excitement and pride in the brand-new car she had just purchased. “I believe I got just 17 miles to the gallon on the trip out here. Which I think is very good for a brand new car, don’t you?”

At a time when most women in the US struggled to break into the workforce and earn equal pay for equal work, the Hormel Girls achieved a level of financial security and success.

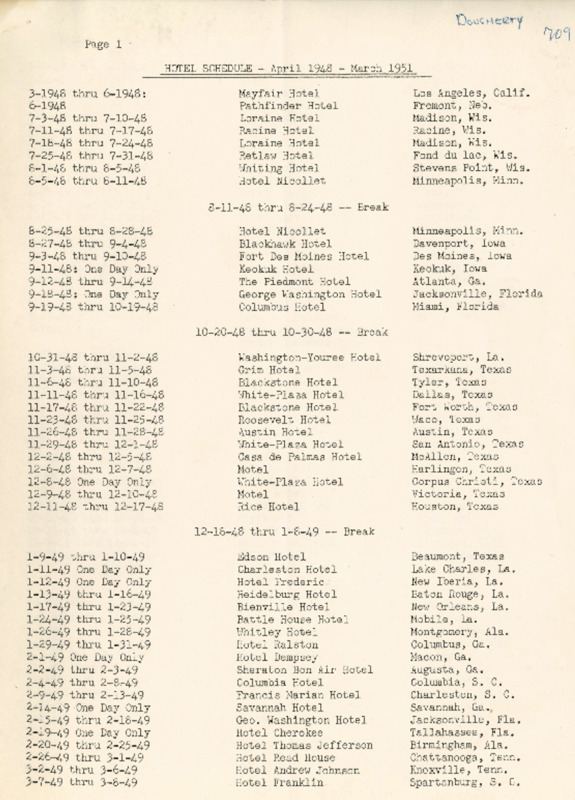

The women traveled all over the country earning a solid wage, but the work was rigorous, challenging, and at times demeaning. Beyond a demanding touring schedule, choral practices, and performance drills, the Hormel company required the women to sell canned meat at local grocers. They were also expected to maintain a beauty standard that complied with Hormel’s marketing strategy and image, with the women subjected to regular "weigh ins" before each performance.

Many of the Hormel girls considered themselves lucky for the opportunities available to them. However, by today’s standards some of the practices employed by Hormel's marketing team would be considered demeaning. The excessively long hours, pressure to meet quotas, and enforcement of a standard of physical beauty all reveal how women still faced hurdles in the struggle for equality and respect.

Over the span of seven years, more than 60 women joined the Hormel Girls and headed out on the road. For some, the mental toll of work and travel was tough, especially for those with strong connections to home and family.

Throughout her letters, Eleanor Jones made it evident she thoroughly enjoyed her job and the opportunities that came with it. At the same time, she was often quite homesick for her previous life and family in small town in Wisconsin. In 1948, she wrote to her parents to express her regret at not being able to make her grandparent's upcoming 60th wedding anniversary. Traveling with the Hormel Girls often meant missing important milestones or family events, something that made the friendships the women forged while traveling all the more meaningful.

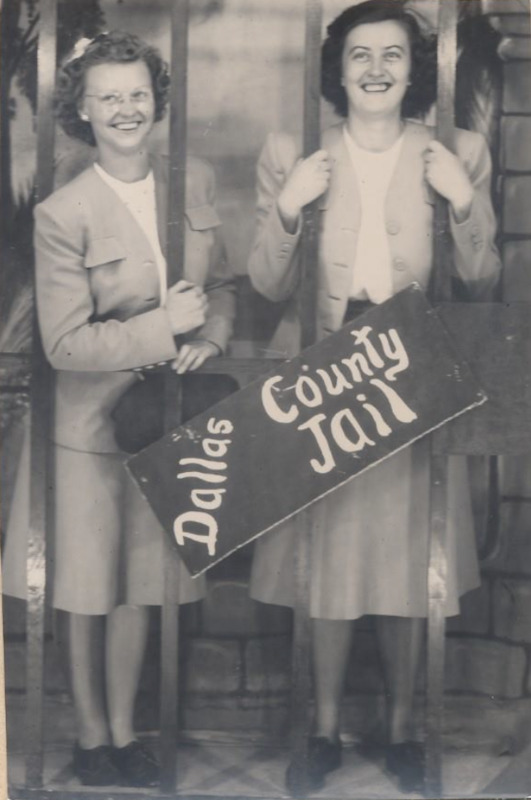

The friendships the Hormel Girls forged on the road proved to be significant and enduring. For years, the women spent countless hours together: practicing their instruments and routines, driving for long stretches, selling products in stores, and recreating in any free time they could spare.

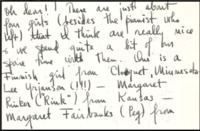

The group traveled together in a caravan of shiny white Chevrolets, making their way across the United States. After cycles of grueling work, the women would enjoy time off, during which they would break off into small groups and travel in the area where they were stationed. It is evident in letters between members of the group that the women shared emotional connections and close bonds, far beyond that of simple colleagues. For some—like Eleanor and her best friend and fellow Hormel Girl, Grace Shipley—the bonds they created extended far beyond their tenure with the group.

After meeting at a Hormel Girl training in 1948, Eleanor and Grace were inseperable, and the years they shared in the band became an incredibly meaningful life-long friendship, lasting over half of a century.

Letters from Eleanor to her parents detail her excitement to be part of a tight knit group of friends that shared adventures, laughs, and heartaches, and in particular her strong bond with Grace.

When they were not traveling in the same caravan, Eleanor and Grace wrote to each other regularly, always signing their letters with loving remarks and greetings. While on the road together, the women spent any well-earned time off laughing and exploring together, illustrated in pictures of the two beaming while posing for pictures at the Dallas County Jail in 1950.

After sharing awe inspiring careers, the women also shared their lives with one another. The settled together in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, purchasing the house they would share until Grace death in January 2017.